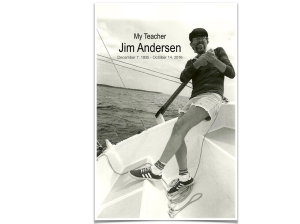

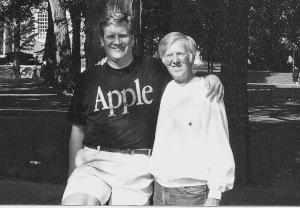

Teachers are an important part of my life. Early on I learned to seek them out. Welcome them when they appeared. Thank them for finding me. Accept their teachings. See the meaning in our shared experiences. Below I honor a teacher of mine.

The events memorializing former President George H. W. Bush were solemn and pageantry-rich. Much like the events memorializing the 38 presidents who preceded him in death. This is not surprising since Bush, like his predecessors, had, soon after taking office, helped put in place the plan for the events following his death that commemorated his life and presidency.

The events memorializing former President George H. W. Bush were solemn and pageantry-rich. Much like the events memorializing the 38 presidents who preceded him in death. This is not surprising since Bush, like his predecessors, had, soon after taking office, helped put in place the plan for the events following his death that commemorated his life and presidency.

Bush’s plan—thick, thorough, and quite specific—contained details for assorted arrivals and departures and the requisite trips by train, plane, and motorcade. It set aside time for his casket to lie in state at the US Capitol. Arranged for a state funeral at the National Cathedral and a private one at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston (funeral site for Bush’s wife, and former first lady, Barbara who died last April). According to the plan, interment was to be at the George Herbert Walker Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas. Where he would lay alongside Barbara and their daughter Robin.

In the plan there were requests unique to Bush and his family. Naming people to eulogize, sing, read, and officiate. Specifying songs and scriptures. Among the requests, was a provision calling for Sully, his service dog and “member of the family”to sit by his casket. As well as for the Oak Ridge Boys to sing Amazing Grace, and granddaughters to do readings at the state funeral.

Each event and every transition had a time, a location, and a person in charge. All designed—as has been the custom since the death of our Nation’s first president George Washington—for putting aside partisan differences, forgiving faults, honoring contributions, and celebrating the shared history of a presidency.

Since first drafting his plan nearly 30 years ago, Bush would periodically review it. And if he wanted revise and update the plan. The final review took place shortly before his passing at home in Houston, Texas on November 30.

The up-to-date status of the plan affords us a glimpse into what—at the end of a life that ranged from the skies of the Pacific during World War II to the Oval Office at the end of the Cold War to a heavenly reunion with Barbara his beloved wife of 73 years—mattered most to our 41stpresident.

Such a glimpse reveals that character mattered to Bush. Not just at the end of his life, but throughout. In an early letter to his mother, Bush laid out what he expected of himself, “Tell the truth. Don’t blame people. Be strong. Do your Best. Try hard. Forgive. Stay the course. All that kind of thing.” That kind of thing that he expected of himself was, in life, a source of much inspiration for those of us who worked for him, and in death, fertile fodder for tributes, anecdotes, and fond remembrances of a special man.

Doing good mattered to Bush too. As recent events and tributes made so clear, public service was a high calling for Bush. And politics were his chosen means for doing good. Conciliation, common sense, dignity, navigating the extremes, and love of country were the hallmarks of the ways that Bush did good.A prolific note-writer, Bush was unrepentantly respectful, even of media.

During the service at the National Cathedral, as tears flowed freely down the faces of family, friends, and colleagues, it was by plan, not accident, that every eulogist Bush had personally selected used their limited time to remind folks that humor was a serious matter for their former president, friend, and father

In a history making eulogy, George W. Bush said of his father, “He loved to laugh, especially at himself. He could tease and needle, but never out of malice. He placed great value on a good joke…” And friend and former Senator Alan Simpson said, “The punch line for George Herbert Walker Bush is this, you would have wanted him on your side. He never lost his sense of humor. Humor is the universal solvent against the abrasive elements of life.”

Of the many things that mattered to Bush, family was the one that mattered most. It was the north star of his life. He was at the center of his family. They—6 children and wife Barbara—were the center of his universe. The family house on Walker’s Point in Kennebunkport, Maine was their refuge.

It is a high tribute to Bush that his children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren effusively express love and admiration for their Poppy. Calling him a “man of the highest character” and “the greatest human being that I will ever know.”

It is human nature to remember the last thing a person does. In the case of George H.W. Bush, him finalizing a plan for the events I, like you, experienced following his death gave me much to remember about what mattered to the man and in his life. He also gave me much to ponder about my life and myself. And what learned from him.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Note: This is the 3rd post in the My Teachers series. Please click the subscribe button on the right side of the blog page to be notified of future posts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.